I finally read the New Yorker’s piece with Rivendell Bike’s Grant Petersen, “The Art of Taking it Slow.” In this article, Petersen expresses his distaste for modern racing bike culture, encouraging people to prioritize comfort, style, and ease. Living in Fort Collins, Colorado, a town where most people at least have a bike, everyone seems to have their own opinion on biking.

I grew up on a bike. From my very first bike that my dad spray-painted DIY camo, to racing BMX, to mountain biking, to commuting to high school, I’ve dipped my toes into many of the biking subcultures. In my experience, these subcultures were all intense. Full of gear-obsessed, rush-chasing bros, with expensive bikes and what I would call elitist mindsets.

It was fun, don’t get me wrong. But eventually I got tired of the all-or-nothing mentality of each of these groups. I’m the kind of person who loves to try things out. To get in to many different things, casually. If I do commit to something, I love to geek out about gear and such, but never in a competitive way.

After a time in each type of biking, life would seem to catch up to me. I was only able to do them because my dad had bought the bikes (with deals from his work). Once I became an adult, burdened with labor of up keeping a bike, or the cost of paying someone else to, I slowly faded away from biking.

I think this happens to a lot of us. We are pushed—socially, economically, infrastructurally— to a car. “It’s just easier,” I told myself.

Bike as Transit

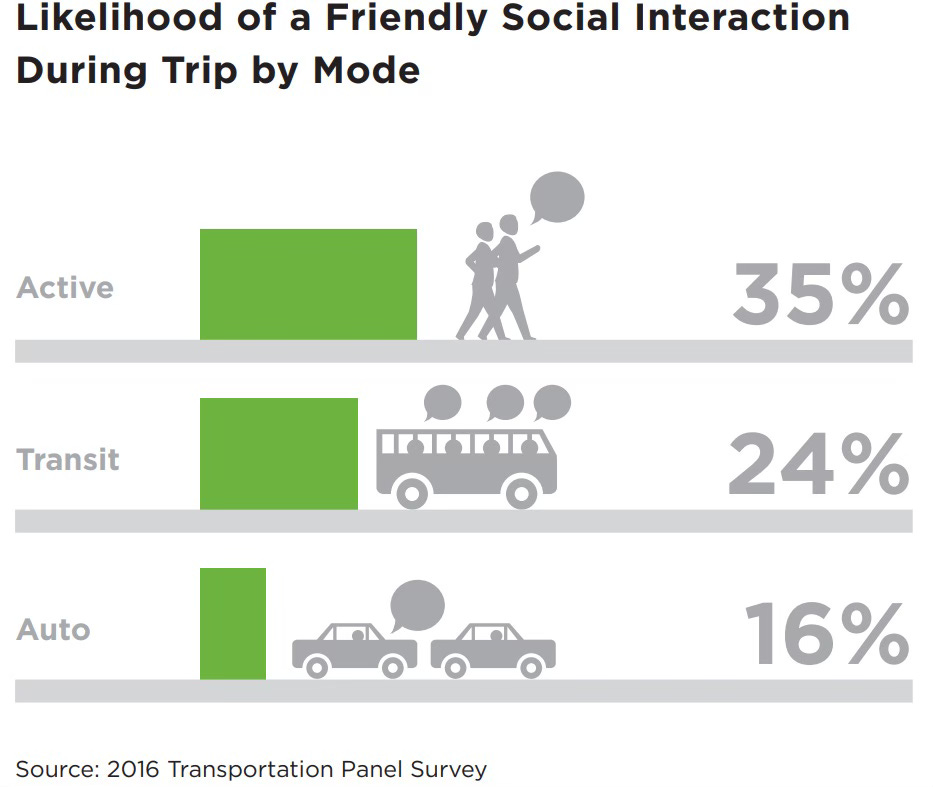

People ride bikes for different reasons exercise, yes, but also as a form of transport, necessity, to get groceries home, or as leisure.

There’s a mentality in Fort Collins (that I have been guilty of) that everyone should bike to work and if you don’t you are killing the planet. I hate to be that guy, but it bears mentioning that this mentality is a) ableist because not everyone can ride a bike. People who are disabled, have different body types, or other limiting respiratory conditions physically can’t bike, and b) it’s classist because not everyone can afford a thousand-dollar bike, let alone afford the upkeep.

However, the mentality that everyone should bike does reflect, I’d like to think, a genuine desire for alternative transportation to cars. If we’re being honest, the transportation solution will be much more than just everyone biking.

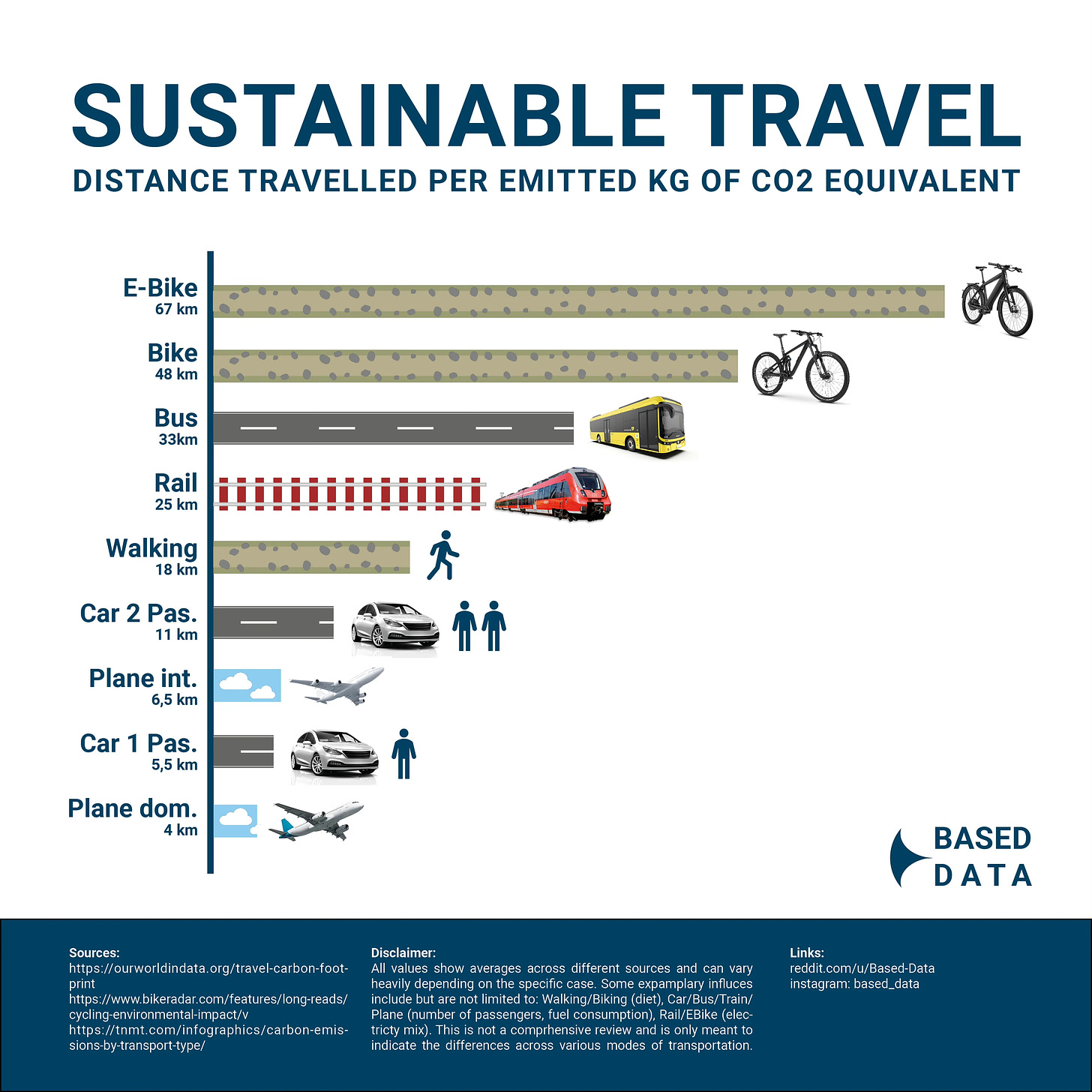

Biking has so many limitations as a form of transportation, I actually think it should be at the bottom of the list. First, you have to be physically feeling well and strong enough to get yourself wherever you want to go every single time you want to travel. It also still necessitates roads albeit smaller ones and is somewhat weather dependent. As long as cars are still around, it’s dangerous and even still without them.

Bikes are also limited to one (or two) persons at time, and are usually purchased and owned by each individual. On the other hand, public transit modes are more efficient space-wise, more accessible, and can be provided by a city, though they emit more carbon, and are less private than a bike.

This article from Peopleforbikes.org concludes, the best solution for an alternative to driving is for cities to adopt integrated public transit, biking, and walking systems.

Realizing why we bike and that it isn’t this cure-all for the transportation nightmare that car companies have created for us is one step along the way to freeing us from bike elitism.

Bike as Hobby

Fort Collins is a town with a very particular kind of hobbyist. Hobby might cease to be an accurate term, because it edges on the line of obsession. The hobbies of choice in this town are all fairly cost-prohibitive—fly fishing, skiing, camping/backpacking. Don’t get me wrong— I love most of these things. And I love geeking out about gear. But the ability to be into any of these activities casually doesn’t really exist. You must be a fanatic, well-off, with time, and lots of it.

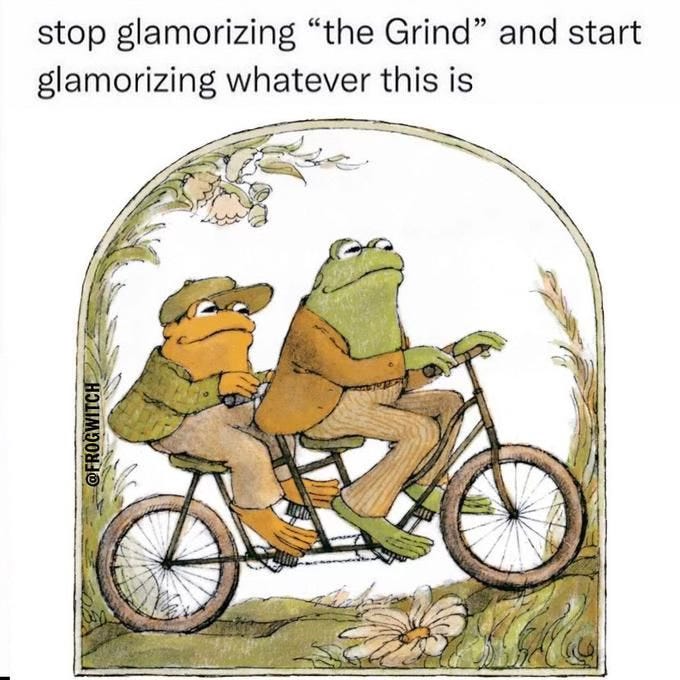

“Hobby” is almost a diminutive term for things we do that bring us pleasure. What would you do if you didn’t have to work? My guess is, there would be a few hobbies in your answer. Hobbies to me are things I’d always rather be doing while I’m at work. They are the things I do that make me feel good. Feel Human. They are things I do to take back my time from the capitalist machine. So, if possible, I’d like to keep them from that machine as much as possible.

Without putting too much weight onto one person, I think Grant Petersen embodies a need people have to engage in a hobby casually, definitively un-intensely. There’s a reason people all over the world organize “Riv Rides” and S24O’s (sub-twenty-four-hour-overnighter).

While I get some people’s eye-rolling response to Petersen’s cult of personality, I think the proof is in the pudding: people love this type of biking.

I’ve recently got back into biking. It began slowly. I’d check out friend’s builds on Instagram. I followed Rivbikes, not even knowing exactly what it was. I watched friends in Minneapolis go on rides with Genosack. I was particularly struck by Genosack’s rides for Palestine—that biking community could be more than spandex and comparing carbon forks. That was something I could get into.

So when my best friend told me he was gonna get into biking, I took the opportunity to fix up my grandpa’s old Peugeot touring bicycle I’d kept after we cleaned out his house following his death. I fixed it up partially using used parts I got from the local Bike Co-op, a treasure trove of stripped frames and endless parted out pieces just waiting for the perfect home.

While doing this, I felt the pull. The pull to make lists of the “best” gear. The most expensive parts. But each time I looked up a part, it felt wrong. Frivolous. Contrary to the whole culture that had pulled me back into biking in the first place.

There is something gratifying in resisting that urge. The urge to elite-out. I’m learning that, for me, it is better to have something special, than something technically the best.

Time

There is friction I feel with the term “taking it slow.” Principally the fact the I don’t have any fucking time to take it slow. I have to work or I have to recover from work, or I have to prepare food for work. Leisure feels more like a check off my to-do list than true free time.

The MLB recently imposed a pitch clock in an effort to make its games more exciting, and to make them go faster. Several ballplayers met this rule change with skepticism that it would complicate their already difficult jobs. While the jury may still be out on whether or not it actually enlivens the games, the message this move sends is clear: let’s speed up the leisure.

From this perspective, Grant Petersen’s assertion that we should take it slow, feels like a freeing, even revolutionary sentiment. To buy less, lose track of time, to bike for the experience, not the competition. It feels right for me. And, because of the constant messaging that I either need to speed up my leisure, or track it to compare to others, or to buy the next best thing, riding at a leisurely pace to the park on my hodgepodge franked-bike feels empowering, and more freeing than anything I could imagine.

Taking Back Pastimes

I titled this section partially in jest. To be clear: I think every type of biking is valid. If racing, spandex, Strava personal bests are your thing, I genuinely don’t want to yuck your yum. I simply think that, in places like Fort Collins, the message gets sent to people that, unless they have x gear or y intensity, biking is simply not for them.

This is why I jokingly implore us casual hobbyists to take back our pastimes from the elitists. This goes for every hobby, I think. Most of us won’t be able to afford the “best.” But maybe there are other variables that matter more to us than technical quality. Maybe there is a uniqueness factor. Or simple practicality.

In my view, if you like something, and you think it’s good for the world, you should want to make it as accessible to others as possible. That means cheap≠bad! A cheap bike that works still gets you to the park. You can still learn to play guitar on a cheap guitar.

Capitalists fear pastimes that makes them no money. Petersen himself admits that Rivendell could charge twice the price for their bikes but don’t because that would make people “get precious” and not ride their bikes. It’s clear that the taking it slow mentality and Rivendell in general’s goal is to make biking more accessible. Engaging in hobbies this way proves that there is more to these things we do than buying new toys. To me, it’s not even necessarily to take back our pastimes from the elitists themselves, but from the capitalists who seek to turn our love for leisure into their cash cows.

I do see the irony in talking about making biking accessible while talking about Rivendell. Their bikes are expensive. But my point is, it doesn’t have to be. It can be whatever you want. Rivendell is expensive because of the quality and how small they are. If you want to spend three grand on a build, and you have the money, you should do it. But you can also get a good bike for under a hundred bucks on marketplace or craigslist. Or from your dead grandpa.

While some people call places like Rivendell a cult, and that definitely has merits, my point is not that Petersen’s view is the best or only view on biking or other hobbies. Rather, I think that we could learn from Petersen that there is something powerful in doing our own thing, going against the current, liking what we like for no other reason than we think it’s cool, and it makes us feel good.